Fall Cattle Journal 2025 | Darling Creek Ranch: Multi-Species Management

“Conservation means preserving natural resources in their best state and improving on that.” –Dan Anderson

Conservation is a family legacy for Dan and Sharon Anderson, who own and operate Darling Creek Ranch, LLC, with their family near Meadow, South Dakota. For Andersons, conservation means preserving natural resources in their best state and improving on that.

“Conservation has always been on the forefront of how we manage our rangeland and our resources,” Dan said. “We don’t want to degrade or deplete the resources we’ve been blessed with, but to try to improve them; that is conservation. We’ve been blessed to have these talents God has given us to try and nurture the resources on the ranch.”

Dan and Sharon purchased the ranch from Dan’s parents, Jim and Nora Anderson, in 1990. A passion for the land they steward has burned strong for generations in the family.

Jim served on the Perkins County Soil Conservation board for 48 years.

“His interest in conservation started as a young man, and we boys picked up on it at a young age,” Dan said.

“My dad improved the ground from when he bought it, we have improved the ground since we took over from him, and we hope the next generation improves it even more. The important thing is to keep learning.”

Dan and Sharon are confident that the next generation will continue to progress in improving the natural resources on the ranch. Their family includes four adult daughters, two sons-in-law and four grandchildren: Danci (Bryce) Baker with Quinn and Rylan, Danika (Kevin) Schmidt with Cody and Blake, Dantae Anderson, and Danessa Anderson. All are involved in the ranch. The need for a transition plan led to the creation of Darling Creek Ranch, LLC in 2018.

“We’re preparing the next generation to keep going. They will make improvements, take advantage of knowledge gained, or create something that can be shared,” Dan said.

“We aren’t concerned that they do things the same way we have, in fact we hope they don’t do everything the same way we did,” Sharon said.

Dan and Sharon love the ranch, the livestock, and truly enjoy the work they do every day.

“That’s all I ever wanted to do,” Dan said. “I could have gotten a job in town but my lifespan would have been very short. I knew from a young age that I would either work on a ranch or have my own. I love what I do. I enjoy being out in God’s creation on a daily basis.”

Cattle and sheep bring diverse benefits to the operation. Andersons run smaller frame sized, easy maintenance cattle with Red Angus and Gelbvieh genetics. Heifers and cows are pasture bred and calve on pasture. Human intervention during calving is rarely necessary. All beef cows run as one herd throughout the year except for a 45-day breeding window when certain bulls are used on certain female groups. Calving begins around April 20, coinciding with lower feed demands and fewer weather-related risks for newborns.

Dan has always loved working with the animals on the ranch.

“Spring is my favorite time of the year with the babies coming; I love being around the newborn calves and lambs. When you do what you enjoy you never work a day in your life.”

Ewes begin lambing around May 15. Ultrasound technology identifies ewes carrying multiple lambs, and Andersons sort these off to lamb in or close to the shed so they can provided assistance as needed. Ewes carrying singles lamb on grass. Yearling ewes are split off into their own flock for lambing so they have plenty of space to learn to mother their lambs for the first time.

Calving and lambing on grass puts more nutrients directly into the pasture rather than piling it up in the corrals.

Andersons shear in the fall. Wool growth on the ewes accumulates over winter and provides warmth and protection for lambs if cool, wet weather occurs during lambing. Mothering instinct stays stronger on ewes with more wool since their bodies are not stressed by cold, wet weather.

The flock is a combination of Merino and Rambouillet genetics. Andersons select for high comfort level, fine wool of 19 microns or less. Their wool goes almost exclusively into U.S. military clothing. Traits such as multiple births, wool fineness, fleece weight, and staple length are documented annually for selection purposes.

Fall is Sharon’s favorite season.

“Spring can be busy; by fall, things have slowed down a little. I enjoy the colors on the trees, and usually we have good weather. It’s nice to see the calves and lambs looking good.”

A year-round grazing strategy is in place for the sheep. The cattle receive some hay during the winter. Sheep receive some grain as an energy supplement, but no additional forages beyond what they have available on pasture.

For Andersons, financial resilience is directly tied to ecosystem resilience.

Rest and recovery periods allow grass roots to go deeper into the soil.

“The deeper the root goes, that’s a canal for water to get to that depth,” Dan said. “It also opens the soil up and helps in migration of nutrients upward and downward as moisture follows that root.”

Rest periods also encourage native grasses and other plant species to flourish.

“We’re finding big bluestem up on the hillsides and hilltops,” Dan said.

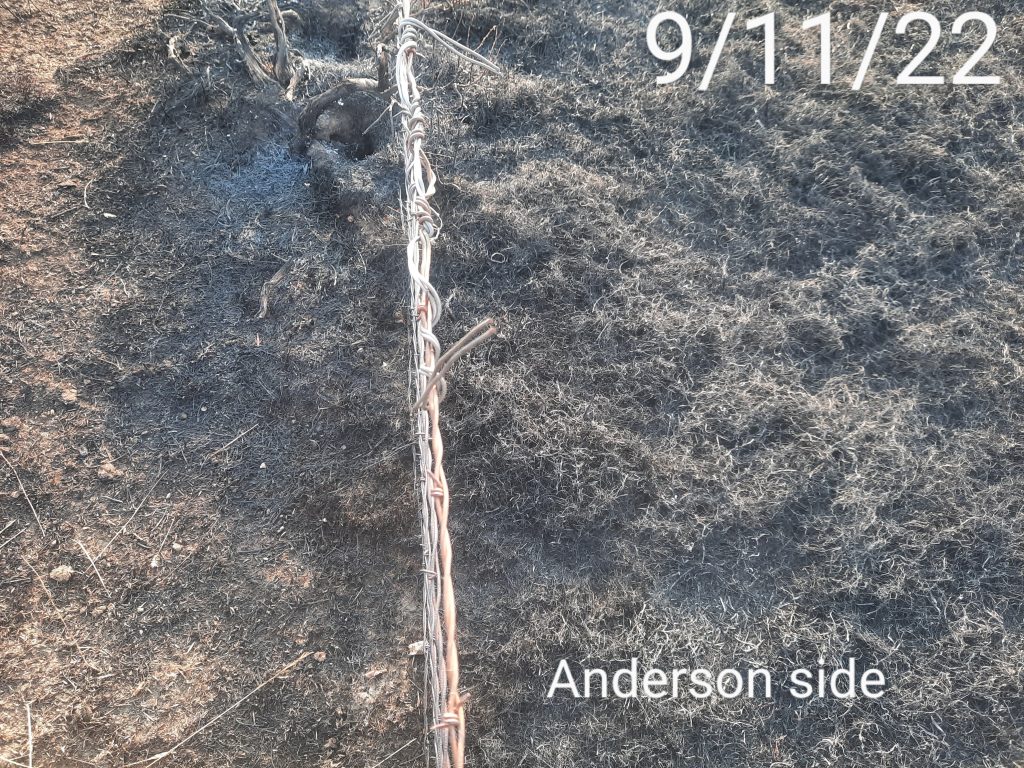

In 2021 a small fire burned across about a half mile of Andersons’ pasture.

“Sometimes it takes adversity to realize what you have,” Sharon said.

“The crowns of the grass looked kind of like black wool, and we didn’t understand why it looked so different from the pasture across the fence even though the grass species were the same. Our range specialist told us that it was because we had more soil moisture, so the grass didn’t burn right to the ground,” Dan said.

In an environment subject to major extremes and wide temperature swings, no two years bring the same weather patterns. Andersons have a drought plan written down, but “we don’t have a plan for excessive moisture,” Dan said. “We kind of wing it when that happens.”

“On wet years, we’re right at double the stocking rate of the historic carrying capacity of the ranch,” Dan said. “Last winter I figured that over a ten-year period we averaged a seventy percent higher stocking rate. This has allowed a daughter to come back to be with us without buying another ranch.”

“We’ve been trying to do that for generations,” Sharon said. “There’s always enough work on the ranch but not enough income. It’s hard to tell bankers that in our area, off farm labor is a long ways from the ranch and it doesn’t pay. I was able to teach at our little country school nearby and I didn’t make a lot of money, but Dan always said, ‘She saves a lot of money.'”

Providing an internship every year gives Andersons an opportunity to share what they’re learning about resilience and sustainability, and it provides them with some needed extra labor during lambing season.

“We thought it was a great opportunity to give some young people interested in range management familiarity with some of the things we do,” Dan said. “Experiencing mob grazing, monitoring pastures, exposure to multi species grazing, and a strictly ranching operation in our short grass country are all great benefits, even if they don’t go into production agriculture after they leave.”

“Even our grasses are a lot different than what most of the interns have seen previously,” Sharon said.

“To survive you have to be adaptable,” Dan said. “It’s crucial to be adaptable to new things, to changes; every year is different. On the ranch you have to adapt to changes in weather conditions, economic conditions; we don’t do the same thing over again very often.”

Andersons were among the first ranchers in northwestern South Dakota to apply high stock density/short duration grazing techniques, also known as mob grazing.

“You build a paddock for one-day of use inside a pasture that might typically offer four to five weeks of grazing. If you have a grazing wreck in this paddock over the course of 24 hours, you’ve affected 1% of your land at most,” Dan quoted his friend, Pat Guptil. “If you have that same wreck at the original pasture size over the course of four or five weeks, you have hurt that land’s productivity for years and impacted 10% or more of your grazing resource.”

Every ranch is different, everyone’s livestock are different, and every family has different needs. All of these factors need to be considered when making management decisions. Andersons believe it is good to look at what other people do and then figure out what works for you and your family.

“We do things to the extreme, for instance, with mob grazing and moving livestock every day,” Sharon said. “We’re not saying everybody has to do what we do, but everyone can do some little thing to make things better. We have picked up ideas from other people, some worked and some didn’t and we tweaked some things. We’re never going to stop trying new ways to make the ranch more productive, and the next generation is going to pick up where we leave off.”

Andersons have brought the same management practices to their allotment in the National Grasslands. They were the first members of the Grand River Grazing Association to bring sheep to their permit, the first to use temporary poly wire for cross fencing, and made the first move from season-long to rotational grazing use on their permit.

Andersons grazing rotation does not co-mingle the sheep and cattle due to risk of malignant catarrh fever, hosted by sheep, deer, and rabbits but potentially lethal to bovine animals. They provide a 45-60 day rest period between cattle and sheep grazing the same grass. Dan experimented one season with by immediately following cattle with sheep. They were not satisfied with the lambs’ growth that year, and suspected that fouled forage may have limited their feed consumption.

“You don’t know what you don’t know; if you aren’t willing to learn you don’t make changes and don’t improve,” Dan said.

While predator protection is an important aspect of the sheep operation, Sharon believes their guard dogs also help keep coyotes and other varmints away from the birds, deer and antelope young.

“We have seen deer with their fawns in our herd of cattle,” she said. “The cattle are always around grazing when the prairie chickens have their leks; I think even just the movement of the livestock helps keep the predators away; they will go on to something easier.”

Diversity in ecosystems benefit land, livestock and wildlife, and Andersons enjoy observing how all can coexist harmoniously and to the benefit of each other.

“You have to have variety to obtain a consistent nutritional level in the grasses,” Dan said. “Our introduced cool season grasses have a short window of nutritional peak and you have to be able to capture that. Most of our native grasses are warm season species, so it works very well to graze the cool season, introduced species in May and June, sometimes starting in April, and then go into the warm season pastures in July, August and September. The cool season grasses often provide regrowth for fall grazing if there is sufficient moisture.”

Andersons believe awareness is growing that farming and ranching need to be viewed holistically.

“If all ecosystems are healthy, sustainability is there to be able to continue producing and harvesting grass and producing high quality protein for human consumption for years on end,” Dan said. “Each of those ecosystems has to work together to be healthy and productive. That helps in the health of the humans, animals and wildlife. Everything works together.”

Looking at the big picture and managing the ranch for sustainability goes beyond work for Andersons.

“That’s what I was put here to do,” Dan said. “There has never been anything else. One way or another you will always figure out how to overcome the challenges. We need to keep sustainability to better be able to feed the world’s populations; that’s the only way the world will survive.”