Screwworm moves northward, US-Mexico summit focuses on corruption

The U.S. Department of Agriculture announced the discovery of a New World Screwworm fly just 70 miles south of the US-Mexico border on Sept 21, 2025. The closest known location of one of these devastating flies had previously been 370 miles south of the border. USDA Secretary Rollins said in a news release that her agency is not counting on the Mexican government to manage the outbreak, but is executing a five-prong approach to get control of the situation.

Since the revelation that the New World Screwworm had moved through the Darien Gap into the nation of Mexico last November, the U.S. has mostly kept the U.S.-Mexico border closed to imports of cattle, horses and bison in an attempt to prevent the movement of the fly into this country. The border remains closed currently, until further notice.

According to Farm News Media, the affected animal was an 8-month-old calf included in a shipment of 100 head of cattle from Minatitlan, Veracruz to Sabinas Hidalgo, in the state of Nuevo León. Only one animal presented an infection, which was treated by SENASICA staff. All cattle received Ivermectin as a precaution, said Mexico Business News.

In a Sept. 25, 2025 Ag Outlook address at Kansas City, Missouri, USDA Secretary Brooke Rollins said that USDA had “boots on the ground” within hours of learning of the case of NWS within 70 miles of the US border. “Unfortunately, what we found was Mexico has failed to enforce proper cattle movement controls in infected regions and is not tending to fly traps daily as promised, which hinder our real time detection capabilities. This is unacceptable. Mexico must fully implement the agreed-upon protocols and must expand surveillance immediately and lock down cattle movement in infected zones,” she said.

The New Mexico State Veterinarian, Dr. Samantha Holick told TSLN that she has not changed her recommendations to the producers in her state. “We are still encouraging producers to monitor cattle and notify us if there are any unusual signs of larval infestation,” she said. New Mexico livestock owners are encouraged to contact their local veterinarian or extension agent to obtain a collection kit upon discovery of any suspicious larva. After collection, either the producer or the local veterinarian or the extension office can send the kit to New Mexico State University for further evaluation.

Holick stressed the fact that the fly had moved northward on a shipment of animals and not on its own. Based off the information she has received, she believes the animal was properly cared for and the larva disposed of.

“The inspection process worked,” she said.

While she doesn’t know if cattle, horses or bison are being smuggled across the border, she said it is possible they can wander across in locations where the border wall doesn’t exist (significant portions of the New Mexico/Mexico border are protected by the wall) or where gates have been opened to allow for wildlife migration. The state is monitoring for stray cattle, she said.

A list of pesticides registered for control of New World screwworm was recently released by the USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. The document can be found at https://isu.pub/NkN3awN.

America First Policy Institute US-Mexico Summit

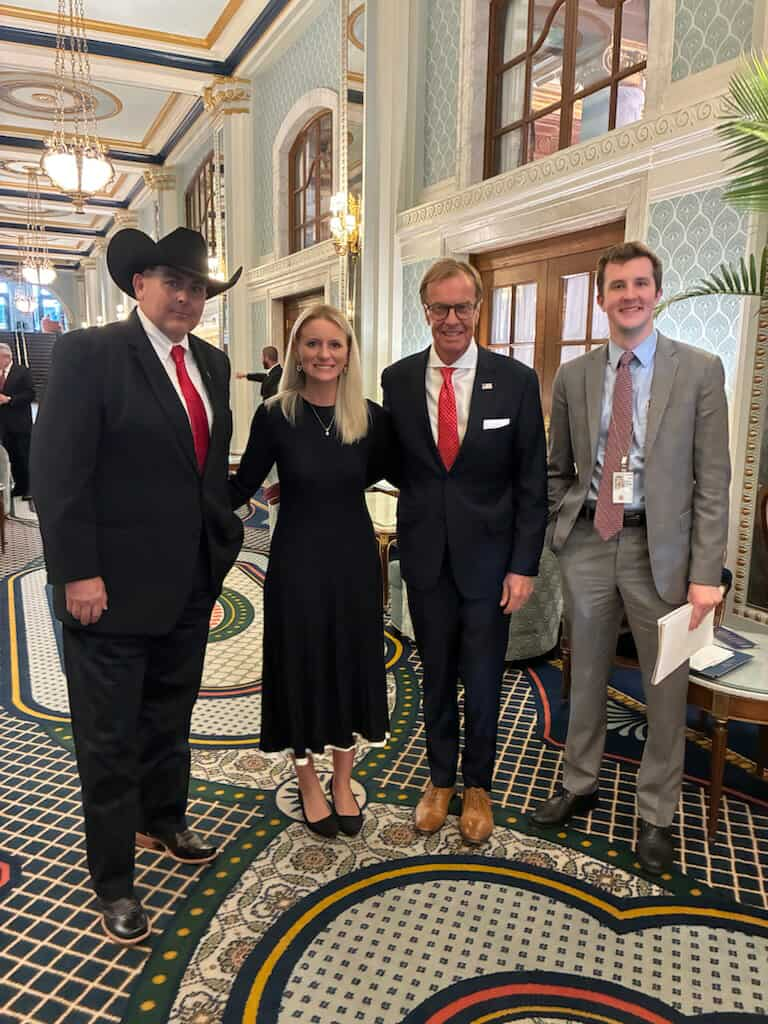

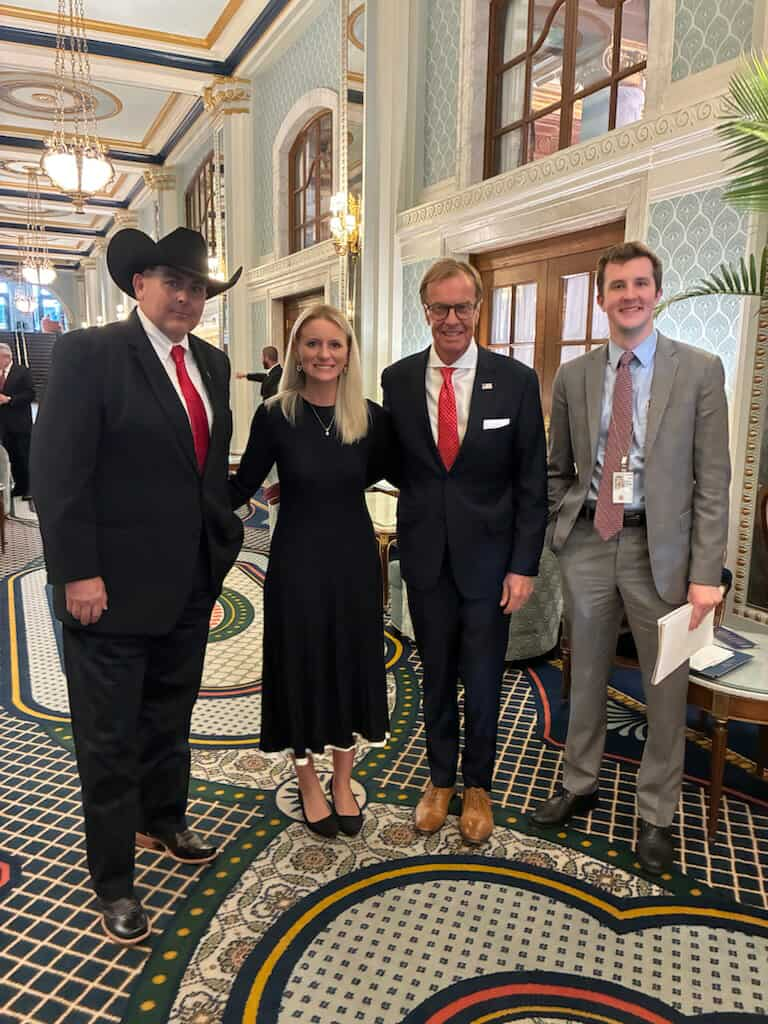

With U.S. – Mexico trade being top of mind for many in agriculture, the America First Policy Institute hosted a US-Mexico Policy Summit in Washington, DC on Sept. 23, 2025.

The summit was also produced by Patria Unida por un México Valiente (translated to United Homeland for a Brave Mexico) and described by Sullivan as “Mexico’s version of AFPI,” The Heritage Foundation and the Texas Public Policy Foundation (TPPF).

Rancher Shad Sullivan, the R-CALF USA Private Property Committee chairman took part in a panel highlighting “Cross-Border Challenges in U.S.–Mexico Agriculture.” Sullivan, who grazes stocker cattle in Texas and Colorado, described AFPI as “a liberty-minded organization that influences and proposes policy through the America First vision.”

While the day-long summit featured several topics, the 45-minute ag panel included Sullivan, Tate Bennett, AFPI director of rural policy; Peter Laudeman, USDA Senior Adviser for Trade and Foreign Agricultural affairs and Kip Tom, farmer and former US ambassador to the UN for food and agriculture.

The conversation at the summit focused on “how Mexico’s failure to manage its agricultural sector is creating real problems for the U.S., from ongoing water disputes and the return of screwworm, to the standoff over GMO corn and threats against USDA inspectors,” said Sullivan.

Sullivan focused on the challenges livestock producers face as a result of trade between the two countries.

“The whole summit was geared toward ‘how do we create a trustworthy trading system with neighbors we can’t trust right now,'” said Sullivan.

Bennett described the impetus for the summit:

“Our two countries remain deeply connected by our history, heritage, culture, trade alliance, a shared border, and the lives of millions of Americans and Mexicans who share family, commerce, and community across that border. However, the last several years have tested the strength and limits of that relationship like never before. The foundation of cooperation has cracked, weakened by cartel violence, collapsing governance, an increasingly confrontational posture from Mexican leadership, and a lack of accountability. For too long, Washington has responded to these realities with wishful thinking instead of a clear-eyed strategy— including with respect to agriculture policy as we have seen threats against the U.S. from Mexico in the form of passing along the New World Screwworm which could contaminate our food supply/ spread to humans and banning GM corn. This conversation, especially on agricultural concerns, was pivotal as we approach a new USMCA negotiation,” she said.

Several citizens of Mexico spoke on the panel as well, Sullivan said. Those Mexican nationals shared the Americans’ concerns.

“How do we get through these barriers that have presented themselves? Mexico has not kept up their end of the deal. The reason is that they are going through the same thing the US has been through. They have no border policy and they are marching toward Marxism. They have a federal government that is split between liberals and conservatives and on top of all of that, the drug cartel has infiltrated their government and exerted significant control,” he said.

“America is a constitutional republic. Mexico is a constitutional republic. Until America and Mexico independently decide to reclaim their sovereignty within their own nations, we can’t have fair and balanced trade. Right now we don’t even have security and control over what influences our political motives here or in Mexico and until the pay to play system is recognized and more highly regulated, we can’t have free and fair trade. We have to get on top of the corruption,” said Sullivan.

The United States-Mexico-Canada (USMCA) agreement and trade in general – including multiple aspects such as agriculture, social influence, economic viability, and darker topics such as human and drug trafficking, were intended to be the main topic of conversation. However, Sullivan said the focus ultimately settled on: whether or not the two countries can form new and better relationships in the face of the Mexican drug cartels’ control over government.

Sullivan spoke about livestock trade, with the New World Screwworm being a focus of his discussion points.

He explained that the return of the parasite is due to multiple issues. Sullivan believes that when numerous workers including border inspectors were instructed to “stay home” during the covid epidemic, protocols for proper movement of cattle between countries was not being followed.

The Center for Strategic and International Studies said the area is vulnerable to illegal cattle movement and Sullivan believes that is just what is happening, hurried along by limited inspector presence during the covid epidemic.

1. Innovating Our Way to Eradication

- USDA is investing $100 million in breakthrough technologies through the NWS Grand Challenge, which will solicit ideas to enhance sterile fly production and develop new tools such as advanced traps, lures, and therapeutics.

- USDA is also exploring and validating technologies like e-beam and x-ray sterilization, genetically engineered flies, and modular sterilization facilities through public listening sessions and ongoing evaluations.

2. Protecting the U.S. Border

- USDA has begun construction on a domestic sterile fly dispersal facility at Moore Air Force Base in Edinburg, Texas. This $8.5 million facility, expected to be substantially complete by the end of 2025, will be capable of dispersing up to 100 million sterile flies per week.

- Planning is also underway with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for construction of a domestic sterile fly production facility in Southern Texas, with a projected capacity of 300 million sterile flies per week.

3. Strengthening Surveillance and Detection

- Since July, USDA alongside Mexico, has been actively monitoring nearly 8,000 traps across Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico. To date, more than 13,000 screening samples have been submitted, with no NWS flies detected.

- USDA continues to disperse 100 million sterile flies per week in Mexico, sourced from the COPEG facility in Panama. USDA is providing support to Mexico to renovate a production facility in Metapa, which is expected to produce an additional 60–100 million sterile flies.

4. Enhancing Public Awareness and Education

- APHIS has published an updated national disease response strategy and is providing training and webinars for federal, state, Tribal, and veterinary partners.

- Outreach materials, including pest ID cards and alerts, are being distributed along the U.S.–Mexico border. APHIS has held over 50 stakeholder meetings and continues to expand outreach efforts.

5. Coordinating with Mexico and International Partners

- Following detections in Oaxaca and Veracruz, USDA closed southern ports of entry to livestock trade after a case was reported 370 miles from the U.S. border.

- USDA is conducting monthly audits of Mexico’s NWS response and is helping Mexico develop a more risk-based trapping plan, especially in Veracruz and along the border. Mexico currently deploys traps in high-risk areas, with USDA support.

- USDA is supporting hiring of over 200 surge staff for trapping and animal movement control in Mexico.

- SENASICA has launched a dashboard

that tracks NWS cases across Mexico. This tool significantly enhances USDA’s ability to monitor the situation south of the border, better assess risk, and deliver more effective operational responses in coordination with Mexican authorities.

More about the NWS

According to WIRED, “in reports submitted to the World Organization for Animal Health, three countries—Costa Rica, Nicaragua, and Honduras—pointed to the illegal transit of animals as the origin of infections in their territories. Honduras detected an outbreak after inspecting 68 horses that entered the country illegally, for example, just 8 kilometers from its border with Nicaragua.”

What seems likely to Kurt Duchez, environmental crime coordinator at the Wildlife Conservation Society, is that the parasite is spreading by road: “It’s the highway route, from Honduras to the Mexican border. We share the Mayan jungle in the north of Guatemala, the cows are not going to pass through the jungle, it doesn’t work this way. The illegal movement of cattle occurs with trucks, they arrive at the border, cross them in wooden boats across the Usumacinta River, and continue their way to the other side.” Smuggling by road through Central America often takes place at night, and the animals moved are often emaciated and in poor condition compared to those raised in Mexico, potentially making them more vulnerable to infection, said a WIRED story written by Geraldine Castro.

The Darién Gap, a roadless, 60-mile stretch of rainforest straddling the Colombia-Panama border. Steep mountains, muddy swamplands, dense forests, turbulent rivers, dangerous wildlife, and high levels of humidity and precipitation make the landscape too hostile for infrastructure and immensely difficult to police, according to the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

The CSIS says the Gap is a long-time haven for paramilitaries, drug traffickers, and criminal organizations operating on both sides of the border, and has in recent years become a major route for migrants leaving Venezuela, Haiti, Ecuador. Immigrants from China, Sub-Saharan Africa and other locations travel to South America for the chance to enter the US via the Darien Gap, according to the CSIS.

Sullivan said he supports and appreciates U.S. Department of Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins’ plan to deal with the New World Screwworm but he encourages a hastening of completion of the sterile fly facility in Texas, which is set to be “substantially complete” by the end of the year, according to USDA.

“I believe with our technology we can have that facility online in a few months. We have to pour money into it,” he said.

Sullivan encourages USDA to find the funding to take total control over the plan to eradicate the pest in Mexico.

“My suggestion is, we pour money into the getting the sterile fly facility online as quickly as possible and budget money for the mitigation program itself. We finance it 100 percent to get control of the migration program ourselves,” he said.

Without an immediate reversal of the fly movement, the parasite is quite likely to enter the United States and cause cattle death and significant expense to cattle owners in treating affected animals, said Sullivan.

Mexican citizens share

A Mexican woman at this week’s summit confirmed the power of the cartel. She told Sullivan that her dad’s ranch had been seized by the Mexican drug cartel.

Sullivan said two women who he shared a table with – one was a Mexican state legislator – shared with him details of how they had saved about 3,000 young women from human trafficking. The women were being trafficked across the border both directions – from north to south and from south to north. “They boldly went in and saved these young women. One told me she has gone months without a paycheck at times, in order to save these women,” said Sullivan.

Lilly Téllez, a Mexican politician and journalist who serves as a state senator for the state of Sonora was a keynote speaker.

“After I spoke about how cattle smuggling has contributed to the New World Screw Worm epidemic, she came up to me and said, ‘you are right. This is happening,'” he said.